It seems fitting that our very first article on The Line would be the paper that inspired New Brookwood Labor College. Jamie Gulley–one of our co-founders–drew materials from the Brookwood Labor College archives at Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University, to write this paper in 2018.

“Brookwood is the only self-respecting, keen, alive, educational institution I have ever known.” -Sinclair Lewis

Introduction

Brookwood Labor College was founded in 1921 by labor leaders and anti-war social reformers to be a college unlike any other (Altenbaugh 70). While most colleges and universities promoted individual advancement and reinforced the elite status of upper-income families, the founders of Brookwood focused exclusively on working-class students and had no interest in helping them achieve individual, personal advancement (Katz). Instead, they wanted to educate students “into their class” (Statement on Brookwood). “The kind of education they wanted… was to educate workers into leadership positions in the American labor movement… to advance their class, not transcend it” (Brookwood Annual Report 1929). In just 16 years, Brookwood produced some of the most important and effective labor leaders of the time.

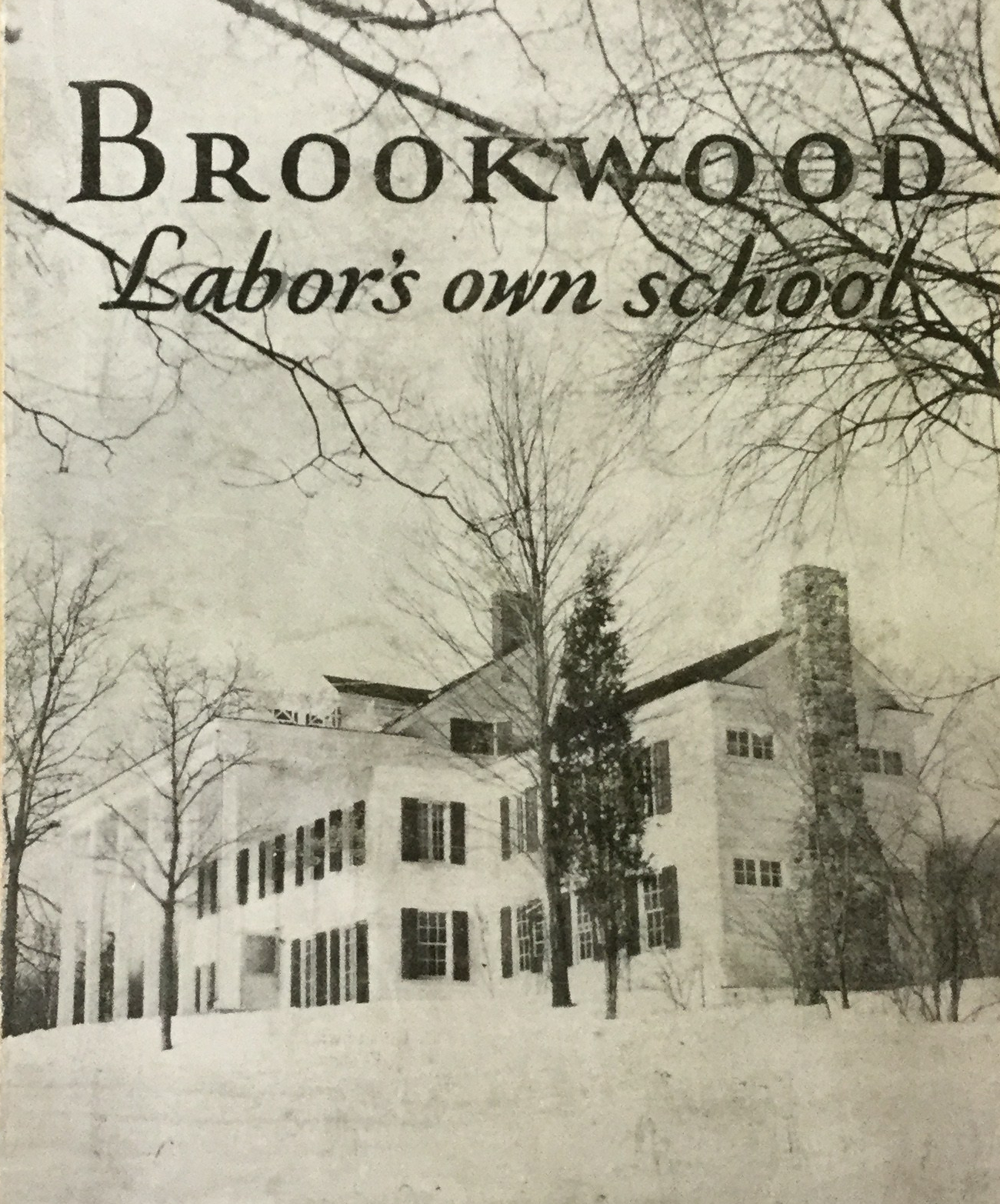

Brookwood, with its 53-acre campus in Katonah, New York, was the first residential college dedicated to worker’s education and was sometimes referred to as Labor’s Harvard (Muste 100) (Eisenmann 234). The beautiful campus was donated by wealthy philanthropists, William and Helen Fincke who, after inheriting a fortune from their family’s coal business, broke away from their comfortable life to be peace activists and “became deeply interested in the labor movement” (Bloom 71). In 1921, the Finckes hosted a conference of progressive labor leaders including, among others, James Maurer of the Pennsylvania Federation of Labor, John Fitzpatrick of the Chicago Federation of Labor, Rose Schneiderman of the Women’s Trade Union League and A.J. Muste, anti-war clergyman and leader of the successful 1919 Lawrence Textile Workers’ strike. Together they determined to launch Brookwood Labor College (Bloom 72). A.J. Muste became the founding chair of the faculty of Brookwood and led the school until 1933 (Hentoff 72). Tucker Smith, an anti-war clergyman who, like Muste, was an activist within the Christian community, Fellowship of Reconciliation, led the school from 1934 until it closure in 1937 (Bloom 72).

According to A.J. Muste, Brookwood’s founders were mostly “labor union people who had come out of the ranks of workers and were concerned to press union organization and to carry on the day-to-day struggle for improved working conditions” (Muste 92). “At the same time, they were militants, severe critics of the narrow craft unionism of the A.F.L. and visionaries who believed we needed a new social order. They contended that the workers would never solve their basic problems unless they strove for a radical reorganization of society, and that such reorganization was possible” (Muste 93).

In keeping with the progressive character of the founders, the conference launched Brookwood Labor College with a declaration of four radical assumptions that demonstrated the vision they had not only for the school, but for the labor movement as a whole (Altenbaugh 71). The assumptions were printed in the New York Times on April 1, 1921:

“First- That a new social order is needed and is coming- in fact, that it is already on the way. Second- That education will not only hasten its coming, but will reduce to a minimum and perhaps do away entirely with a resort to violent methods. Third- That the workers are the ones who will usher in the new social order. Fourth- That there is immediate need for a workers’ college with a broad curriculum, located amid healthy surroundings, where the student can completely apply themselves to the task at hand.”

With this vision in mind, the founders immediately set to work recruiting and training a cadre of workers to assume leadership roles in their unions in the hope that they would usher into being the new social order.

Through word of mouth, advertising, and the active efforts of labor progressives, Brookwood’s faculty and administration recruited promising students from across the labor movement (Muste 100). They would train the students in academic subjects including labor history, economic and political theory and in practical labor skills such as organizing workers, conducting strikes, generating media, securing relief, and writing press releases and pamphlets.

Although Brookwood ceased enrolling students after only sixteen years it had an outsized impact on the labor movement and society. Between 1921 and 1937, more than 500 students graduated from Brookwood and those graduates went on to lead many of the largest, most successful organizing drives in US labor history (Howlett v) (Altenbaugh 96). It is fascinating and relevant for labor today to understand how Brookwood educated its students in a way that bolstered class awareness and indeed pride. At a time when much of the labor movement strove to be small and conservative, Brookwood graduates “called for the abolition of war, the unionization of workers in industrial unions… the organization of the unskilled and semi-skilled workers in the mass production industries and equality of all workers regardless of sex, race or nationality” (Foner 119). Brookwood Labor College served as “a source of inspiration for contemporary activists interested in the revitalization and reformation of a stagnating labor movement” (Foner 119).

The most important elements of the Brookwood model–and indeed those that created graduates who were dedicated believers in the power of labor to create widespread social change–included: (1) the culture and community of Brookwood embraced by faculty and students throughout the school experience, (2) the curriculum and methods of teaching used by Brookwood faculty, including a focus on student action and work product rather than grades, and (3) the labor drama program and field work programs that spread the ideas developed at Brookwood throughout the labor movement.

Culture and Community

Admissions

In the early years of Brookwood, the majority of students entered upon the recommendation of the founding members of the community (Muste 100). As time progressed a more formalized admission policy was designed to ensure the students recruited to Brookwood would fit within the culture that A.J. Muste and the faculty were cultivating. Brookwood faculty were clear both about the students they wanted and those they did not want. According to Muste, the faculty wanted students who could be recruited “into the critical ranks of organized labor”, students who would be willing to challenge unions and union officials.

“They did not want the students who… came to Brookwood for resident study to become professionals or intellectuals. They wanted them to go back to the shop or mine, to be active in local unions, perhaps, in time, to be elected to higher union offices but to remain ‘in the struggle’- not to acquire an itch to get on the payroll- to retain a fighting edge and a dynamic realism (Muste 94).”

Preference was given to applicants who had held union membership for a period of at least one year (Brookwood Pamphlet). This requirement was a minimum for applicants; in reality, the quality of applicants was so high that students often had many more years of experience (Brookwood Entrance Requirements). In addition to meeting the service requirements, each applicant was required to submit three character references, including “at least two of whom [were] persons in responsible positions in the labor movement, who [were] able to vouch for his loyalty to organized labor” (Brookwood Pamphlet).

While much weight was given to the kinds of students who would be admitted to Brookwood, it is notable that prior educational achievements were not necessarily required. In fact, Brookwood made special efforts to ensure that all students were able to fully participate in the life of the school regardless of background. Brookwood even employed English and elementary education tutors for students lacking academic skills (Report to Executive Committee 1927). According to Muste, the students “had for the most part been compelled to go to work on graduation from the eighth grade, if not before. Quite a few were recent immigrants… and accordingly had language difficulties” (Muste 93). The recruitment pamphlets made specific mention that “no examinations or specific preparatory schooling [were] required” (Brookwood Pamphlet).

In addition to recruiting students from a variety of industries and union backgrounds the school faculty and student body were both proudly co-educational and by 1923, multi-racial (Norton). Brookwood’s recruitment pamphlets and internal documents declared, “Brookwood is a strictly co-educational institution and affords an absolute equality of opportunity and responsibility as between the sexes” (Brookwood Pamphlet). Not only did Brookwood actively recruit workers of color to attend the school, faculty and students hosted conferences on the issue of race in the workforce and such conferences called for the total elimination of discrimination by race within the labor movement (Howlett 248). The decision to operate on a multi-racial basis was not without moments of turmoil. Lee Stanley, Muste’s secretary, recounted how one student from a racially segregated railroad brotherhood in the South reacted when he discovered his class was integrated. “The student had never lived with or eaten with a Negro, made a big fuss about it and declared he wasn’t going to. He was told that he either did or he could leave. He stayed and became and very friendly with her. That taught him a lesson” (Altenbaugh 142).

Brookwood’s commitment to opposing discrimination was not confined to gender and race but extended to ideology as well. Students with diverse views attended Brookwood including many whose beliefs differed from the faculty. For example, while A.J. Muste and the majority of the faculty were committed pacifists, many of the students were not. According to one student “strong disagreement erupted among students as to what labor’s attitude… should be” (Howlett 187). Despite the controversy of such a decision at the time, Brookwood also admitted communist students for many years.

“It is the feeling of the Brookwood Executive Board that bringing together young men and women from various parts and sections of the country, having naturally various backgrounds and holding probably various points of view, is in itself highly educational and therefore worthwhile… Brookwood does not discriminate against applicants on account of opinions the may hold (Brookwood Entrance Requirements).”

The intentional commitment to create a co-educational, multi-racial and ideologically open, non-dogmatic culture helped create a model of the better society Brookwood’s founders envisioned (Muste 96). Len De Caux went so far to describe it as having “aspects of a quasi-Utopian colony” (95). For students, this exposure and experience of creating community was instrumental in giving life to what a more just society could and should look like.

Campus

The Brookwood campus was set in a picturesque valley in New York that would become a source of joy and relaxation for students, many of whom came from the coal fields or industrial centers where outdoor recreation was difficult to find. Len Decaux remarked at length about the campus in his memoirs,

“Brookwood was beautiful- if not beyond compare, certainly by compare. To the miner, Brookwood was green, clean, all above ground- no coaldust, no cricks in the back. To the machinist, Brookwood was greaseless days far from the grinding roar of metal against metal…Brookwood was fairytale country to which they were wand-wafted from the square, treeless hills, the trash strewn cement valleys of Manhattan or Chicago (Decaux 95).”

It was in the context of this physical campus that faculty and students worked to intentionally develop a culture and community that would resemble the society they were hoping to create. For the first ten years, Brookwood Labor College was a two year residential program. In the early 1930s, the school implemented a one year program aimed at reducing costs and making it more accessible to students who were increasingly called away by their unions for organizing work (Altenbaugh 224-230). The program was capped by a Chautauqua tour in which the students brought plays, drama, and union songs around the country to union halls, picnics and conventions (Bloom 75).

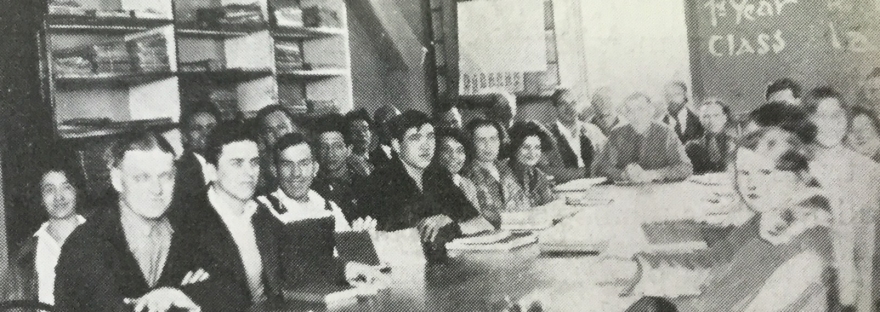

The Brookwood campus was usually home to about 40 students (15- 25 students per class year) 10 faculty and a few other staff who helped in secretarial tasks and in the upkeep of the building and grounds (Muste 99). A typical school year included two class cycles, each 15 weeks long (Howlett 97). Summers were spent back at home, working or engaged in the union activities of the students’ home unions (DeCaux 96). Students attended classes for 3 hours each week per class and twice a week the whole community gathered at the main building for songs and lively discussion about the issues of the week (Howlett 62). Evenings included quiet time for students to read, work on essays and other assignments and to do chores and other work associated with the daily life of the Brookwood community (Brookwood Guide for Students).

It was important to Muste and the Brookwood faculty that everyone in the community continue to be active in the labor movement. According to Muste,

“As teachers and students, we did not think of ourselves as temporarily withdrawn from the labor struggle while preparing for future activity. Geographically, we were off in a somewhat idyllic country setting, and the students were away from their jobs and day to day union activities. But psychologically, we were participants in the economic and political movements of that time. Students continued to attend local union meetings if they were near enough to permit it. Others might travel further if there was a crucial policy decision to be made in their unions, or a strike in progress (107).”

A steady stream of visitors from throughout the labor movement also came to campus (Bloom 75) (Muste 105). Visitors included such notable figures as Nobel prize winning author Sinclair Lewis, Emma Bellamy (widow of utopian author Edward Bellamy), W.E.B. Dubois, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, William Z Foster, Norman Thomas, leaders of the NAACP and the Urban League, and other left-wing political figures as well as leaders from across the spectrum of the labor movement, from William Green, head of the A.F.L. to John Brophy, opposition leader to the John L Lewis administration in the UMW. These visitors kept students current on what was happening in the country and in the labor movement and provoked lively discussions about the important issues of their time.

First Day/How to Succeed at Brookwood

Once admitted to Brookwood, students were accepted on a probationary basis and were not admitted as a full participants in the school community until they could “demonstrate within a reasonable time sufficient ability and earnestness as well as comprehension of what it [meant] to be a Brookwood student” (Brookwood Pamphlet). Consistent with the founders’ vision, commitment to the labor movement and toward the mission of building leaders willing to engage in active struggle for a better society–not academic accomplishment–drove the culture at Brookwood. The movement spirit that was glimpsed in the admission process became clear on the student’s very first day on campus.

At orientation, students received a detailed and thorough memo entitled, “Brookwood Guide for Students” which included notes on topics such as chores and campus life, to whom to go to for questions, daily schedule including quiet times, laundry protocols, room assignments, and course schedules. The memo also introduced students to Brookwood’s cooperative living environment. On that first day, the students learned that they would create a cooperative culture of daily life, working together to build roads, repair living quarters, cook and serve meals, and do laundry (Howlett 77). Brookwood bragged about this cooperative living experience in a 1924 report presented at Ruskin College:

“One of the most important factors in education at Brookwood is the community living, which itself presents and offers opportunity to work out the problems of democracy as they arise from day to day work. Nor are any persons set apart as exclusively manual workers, All participate in the daily tasks… (Report on Brookwood Labor College to Second International Conference on Workers’ Education).”

At orientation students gathered with their teachers at the main house for their first “faculty meeting” which opened with songs (Howlett 352); together they sang familiar labor songs and learned new ones. The faculty even introduced themselves and their courses to the students with verse. “There’s A.J. Muste a teacher, he used to be a preacher”; “Dave Saposs tells them stories, About past union glories”; “while JC Kennedy does his stuff and makes them learn their Marx enough” (Brookwood Songs and Faculty Skits). The camaraderie and movement experience in those moments would have been palpable. Songs, drama, and public speaking were all part of the first day activities at Brookwood, but served to introduce the students to a campus culture in which raw, provoking, emotional tools played major roles. At Brookwood, students learned to engage in debate, public speaking, drama and especially singing as tools to create community and solidarity (Altenbaugh 142).

Governance

The cooperative living experience was also visible in the governing structure of the school. Formally, the school was governed by an Executive Committee that included ten labor directors from outside of the institution. The directors included a veritable who’s who of progressive labor leaders–leaders like Fannia Cohen, (I.L.G.W.U.), Abraham Lefkowitz (A.F.T.), James Mauerer (Pennsylvania A.F.L.), John Fitzpatrick (Chicago A.F.L.) and John Brophy (U.M.W.). The board also included representatives from the faculty, students and alumni (Muste 128). In addition to the Executive Committee, the faculty and students each had their own committees and meetings in which they discussed grievances, problems, and ways to improve the school (Brookwood Guide for Students). The students had their own student produced and edited journal titled “The Line” and the student body was known to produce petitions and occasionally even to strike over concerns about the school (Student Body Minutes, Dec. 1929). It was a student petition, in fact, that prodded Brookwood to hire additional tutors for some of the immigrant students who were lagging behind in coursework (Student Body Minutes, Oct 1932).

Brookwood faculty were organized as local 189 of the American Federation of Teachers and met frequently to discuss the curriculum and opportunities for specific workshops and other ways to advance the learning experience of students. In so many ways the organized faculty were preservers of the unique culture of Brookwood. Katherine Pollack and other members of the faculty published numerous booklets for the labor movement, including “The Labor Movement Today” as well as correspondence courses on labor economics, organizing and other topics important to the time. Many key decisions at Brookwood were made collectively by the faculty, including such controversial decisions as asking A.J. Muste to curtail his political activities to refocus on Brookwood in 1932 and the decision to ask popular faculty member Arthur Calhoun to leave the school (Altenbaugh 209). Even after Brookwood’s closure, local 189 continued to produce content and advance the interest of the workers’ education movement, opening its membership to any teachers who wished to be involved in workers’ education (Altenbaugh 230).

Brookwood’s founders and faculty envisioned educating a diverse cadre of dedicated union leaders who would, when they left the campus, be ready and prepared to create a more just society; from the application through students’ last days on campus, Brookwood reinforced the culture and values it hoped to instill in its student body. Brookwood operated under democratic principles and developed a cooperative culture in its daily activities and life. Students, faculty, alumni, and the founders had formal and informal roles to play to bring into being the microcosm of the broader world they envisioned creating through a more active and militant (though explicitly non-violent) labor movement. The movement creation aspects of Brookwood were evident in intentional moments of solidarity–singing together, learning from each other, and embracing differences in background and opinion. When students left Brookwood, they could take with them a visceral feeling for the kind of society the labor movement could create and the knowledge of how to create it.

Curriculum and Teaching Methods

Philosophy and Methods

While community and cooperation defined Brookwood day-to-day life, academics were rigorous and equally important. Brookwood faculty had a strong vision for student learning. The primary aim, according to a 1928 report, was to “develop in students a consciousness of their position and interests as members of the working class, and to make them more intelligent and efficient workers in their unions and in the general struggles of a militant labor movement” (Statement on Brookwood). According to Muste,

“They wanted them to have a picture of the human struggle through the ages, some concept of the working of the economic system, a life-philosophy which integrated satisfaction of the basic psychological needs with devotion to the cause of a new social order, with practical and, if need be, sacrificial and risky daily work for such a new order in working class districts throughout the country (94).”

At Brookwood, there were no grades or report cards and in fact no degrees were awarded to students (Howlett 83). However, it would be incorrect to assume that the classes were less rigorous than classes at other universities; Muste insisted that the work done by students be “on par with upperclass work in [any other] good college or university” (104); the course outlines, reading materials and study guides bear this out–each semester-long class covered a great breadth of material. In the classroom, “students experienced teaching techniques similar to those of traditional colleges and universities. Lectures, class discussion and notetaking were common devices for learning” (Howlett 63).

Muste likened the difference between students at a traditional college and those at Brookwood as, “in the former you had students who did not know anything but knew how to say it, whereas at Brookwood you had students who knew a great deal but didn’t know how to say it” (103). Although Brookwood did not grade assignments, the faculty taught students to put their ideas into words and practice; they expected the students to write many papers and even to publish their completed works (Norton). Such high expectations would have been notable at traditional universities but were particularly impressive given the limited educational background of many of the students.

Brookwood emphasized learning through inquiry; this was evident in the course outlines in which faculty repeatedly and consistently questioned and challenged students on their beliefs and on what the labor movement’s perspective should be on relevant and timely issues. Whether the courses included heavy emphasis on lecture or included a strong field component, most featured lively discussions and engaging assignments that forced students to consider their views on given subjects. For example, in a seminar on labor’s view of war, students were asked to write 2-3 pages on the following question, “Would you support the following types of war? Give reasons for your answers. A war fought by the US? A war fought against colonial independence? A war against a fascist state? A war in which the US was an ally of the Soviet Union” (Howlett 187). Similarly, in the economics course, students were challenged to address open-ended questions such as, “Why does your boss not run the works at 100% capacity every day? How much power has the industrial employer to control unemployment? What do you think of a bunch of workers that go to the limit in working overtime when the employer is willing to take on additional workers?” (Calhoun) This method of using open ended questions and encouraging students to take positions permeated course notes and syllabi from Brookwood and led to endless informal discussions on challenges faced by labor on Brookwood’s lawn each day (Howlett 187).

In addition to expecting students to deeply understand issues and news as they related to labor, Brookwood’s faculty wanted them to learn the tools of the trade, so to speak, for leading their unions. According to Muste, they wanted the students “to acquire what we now call ‘know-how’ in certain fields: how to keep minutes and write resolutions; how to conduct a meeting; how to organize a strike, provide relief, secure fair publicity for the cause, and so on” (94). Students were taught these skills in what were called “tool courses” which often included significant components of field work.

Even before the introduction of the drama program in 1925, Brookwood faculty believed in storytelling as a powerful tool for the movement. In the Brookwood English course, students learned the basics of sentence structure and grammar, then were asked to write and present their own stories to the class (Colby). For example, in some years, students were asked to present their unemployment stories as case histories. While such exercises allowed the students to practice writing and narrative, they had the added value of developing solidarity between students as they came to understand what were often perceived as shameful personal episodes as shared experiences that transcended industries and backgrounds. The results included stories such as, “What Made Me Hold On” and “Searching for Bread” and many other poignant essays that reinforced the culture of solidarity and class consciousness at Brookwood (Howlett 64).

Although the faculty wanted students to develop a militant progressive view of the labor movement and a definitive sense of class consciousness, they sought to achieve it in an atmosphere free from dogma and rejected pedagogical approaches that might “indoctrinate” students with any particular theories (Muste 107). This point was reinforced in a statement written by faculty and students during an episode in which the A.F.L. Executive Committee charged the school with factionalism. “It is not the duty of a school to ‘sell’ facts or theories after the manner of high pressure salesmanship, much less force them upon people, but rather in a discussion of all problems to secure consideration for all pertinent facts and views and scientific thinking upon them as may be possible” (Statement on Brookwood).

Tool Courses vs Theory

The Brookwood curriculum was divided into two types of courses- tool courses and background courses (Altenbaugh 94). Popular background courses included: “History of the American Labor Movement” and “Trade Union Organization Work” taught by David Saposs, and “Advanced Economics” by John C. Kennedy. Other background courses included: “Foreign Labor Movements”, “Modern Industry” and “Labor Politics” which served to educate students while simultaneously instilling a sense of solidarity. The courses served to enable students from various backgrounds and industries see the connections between their struggles (Altenbaugh 94).

Tool courses taught students to organize and lead workers and to run their locals (Altenbaugh 96). The courses included, “Public Speaking” taught by Josephine Colby, “Parliamentary Law”–in which students practiced running union meetings with Robert’s Rules of Order–and “Trade Union Administration Technique” in which students learned to properly maintain union membership and finances records including dues collection book keeping and administration of union benefit programs. In public speaking class, Professor Colby, would ask students to read passages out loud and “would work to improve student’s performance, directing them to hold their heads straight, speak more slowly, pronounce certain words again” (Howlett 64). “Labor Journalism”, taught by Helen Norton, included skills like how to write a story for local newspapers or the labor press and how to publicize union organization work and struggles. Students learned everything from basic grammar and story structures to how to use a mimeograph machines to design and print pamphlets and posters. Students were expected to practice the tools from this class by publishing articles in the Brookwood Review. Further tool courses included, “First Aid”, “Effective Methods of Approaching and Organizing Workers” and seminars on “How to Conduct a Strike”, “Resolutions”, and “Labor Strategy”.

Interestingly, even tools courses like “Labor Legislation”, in which students practiced introducing and passing pro-worker legislation, included key lessons about the need to create a fundamentally different society. For example, the course notes, prepared by board member Abraham Lefkowitz, indicated that the discussion following the lesson on how a bill becomes a law, regarded how the current system, even when labor occasionally succeeds in passing legislation, reinforces class divisions. Students were asked whether it was better to operate within the current system to alleviate immediate economic needs for workers or to apply their energy and efforts to creating a new political system in which workers rule instead. (Lefkowitz).

Labor Drama Program and Field Work

The labor dramatics program at Brookwood Labor College began as an experiment in 1925 (Altenbaugh 102). The class typically met for one hour each week and students would read and produce plays. Students and faculty eventually converted the old barn on campus into a theater (Howlett 82). Through the years, the drama program at Brookwood continuously expanded, becoming a major part of the one year program in the 1930s.

Theater has long been used by progressive movements as a means of organizing the masses and agitating for social change. Use of the theater was a great way for activists to find an audience that would not necessarily attend a political lecture or ordinary union business meeting (Altenbaugh 103). The drama program had the effect of helping students learn oratory and other novel ways to engage audiences about the union movement that likely proved useful in future leadership roles. But the primary focus of the drama program was to serve as another “education tool” to spread class consciousness (Muste 104).

Hazel MacKaye, was hired specifically to launch the drama program at Brookwood for the 1925-1926 school year and the Brookwood Players, as they would be called, quickly produced several one act plays (Altenbaugh 104). According to Altenbaugh, the scripts of the one act plays, dispensed with the normal process of character development and focused on “recognizable symbols” (104). According to Malcolm Goldstein, it was typical for “Agitation-Propaganda” plays, sometimes called, “Agit-Prop” to include “a blend of chanted dialogue and mass movement in which the actors, performing in unison, symbolized the working-class solidarity necessary for the overthrow of the bosses” (Goldstein 34). Due to the cost involved with royalty fees and the lack of plays that could serve as a good fit for the Brookwood Players, students composed plays of their own (Howlett 83). Some of the more popular plays written by the students included, “The Tailor Shop”, “The Starvation Army”, “Mill Shadows”, “Sit Down, “Miners” and “An Open Shop Summer”.

Chautauqua

From 1925 on, the school year at Brookwood concluded with a Chautauqua Tour in which the students would travel to union halls, labor picnics and conventions throughout the country. “The travelling Chautauqua consisted of lectures, songs, mass recitations and labor plays” (Howlett 81). The Chautauqua brought some measure of fame to Brookwood and also served as an important fundraiser for the school (Howlett 82). By 1934, the Brookwood student body divided into three different theater companies and “toured fifty-three cities, covering some forty-three hundred miles, and performed before as many as 14,500 workers” (Altenbaugh 113). In 1935, at the height of the program’s popularity, the Brookwood Players performed 90 times before 20,000 people, (“The Chautauqua Grows”).

Field Work

One of the required components of the Brookwood experience was “field work”. Field work gave students opportunities to put the ideas and tools that they were learning into practice. Field work included a variety of activities based on the opportunities available each year. In 1926, students were deployed to engage in strike activity on behalf of a variety of unions in New York, including the I.L.G.W.U. and the Brotherhood of Railway and Steamship Clerks. Students were tasked with raising relief funds for the strikers, often putting on special performances as the Brookwood Players to raise funds and helped with the clerical work associated with relief distribution and strike activity (Altenbaugh 117). Sometimes students would engage in field work related to union reform activities, returning to their home unions to move resolutions for labor reform or participating in reform campaigns like John Brophy’s ‘save-the-union’ campaign for leadership of the United Mine Workers (Altenbaugh 117). In later years, students adopted the Textile Workers Strike in Passaic New Jersey as a major component of their field work (Howlett 250).

The field work and labor drama programs were instrumental in teaching students the importance of doing the work of the labor movement, as well as in learning the difficulties and limitations of the workers’ struggle. Notably, it was at Brookwood that Roy Reuther and Merlin Bishop, after learning the limitations of traditional strike activity–even those with mass picketing as was deployed in Passaic during the Textile Strike–first discussed the use of “sit down” strikes by unions in France (Howlett 302). As they discussed the strategy with professor Seidman, they were concerned about the “sit-down” because of it would likely be deemed illegal. According to Seidman, however, he encouraged them, “If a sit-down strike can force General Motors to engage in collective bargaining with the automobile workers whereas a walk out would not have that effect, then Brookwood favors the sit-down strike” (Seidman). In January 1937 when the sit down strike in Flint, Michigan began, Merlin Bishop, as the new education director of the UAW, immediately set up a mini-Brookwood inside the plant to educate workers about the movement. And in the tradition of Brookwood, he began the Flint sit-down educational effort with singing (Fine).

Conclusion

In the 16 years that Brookwood enrolled students, it produced more than 500 graduates (Bloom 72). Those graduates went on to lead some of the most important organizing campaigns of the 1920s and 1930s and filled many key roles in the great C.I.O. upsurge of the late 1930s (Bloom 35). Graduate Len DeCaux, became editor of the C.I.O. news and helped direct publicity for the C.I.O. throughout the 1930s (DeCaux 96). Other graduates included leaders of the great Textile Strikes in Passaic New Jersey, in New York and throughout the Southern United States, at Toledo Auto-Lite, the Akron rubber strikes, in the West Virginia minefields and throughout the United Auto Workers and Steel Workers Organizing Committees. Merlin Bishop and the Reuther brothers (Roy and Victor), who led the Flint sit down strike were graduates of Brookwood (Howlett 350). Julius Hochman, vice-president of the I.L.G.W.U., Jack Rubenstein, vice-president of the Textile Workers of America, Emil Rieve president of the Hosiery Workers, and Elmer Cope who would go onto become president of the Ohio A.F.L.-C.I.O., were all graduates (Howlett xii). Students would go onto lead the worker education programs at numerous national unions and to teach at labor colleges in Denver, Seattle, St. Paul and Baltimore (Howlett 296-300). Some students, like Ella Baker, would go onto play significant roles in the Civil Rights movement as well (Ransby 73).

Despite the success of so many of its graduates and its impact on the labor movement, Brookwood ultimately ceased to be an institution in 1937. Scholars attribute the demise of Brookwood largely to economic factors; in particular the Great Depression and divisions–both ideological and formal–in the labor movement which drew funds away from institutions like Brookwood. Brookwood depended on donor support, but experienced economic repercussions from the Great Depression in severely diminished contributions from non-labor sources. Additionally, through the 1920s and 1930s the labor movement experienced an extended ideological debate which led to a formal split in the labor movement between the A.F.L. and the C.I.O. in 1935. This split, which was accompanied by intense competition between the rival federations to organize workers, consumed incredible funds from within the labor movement at the same time that the non-labor sources of income were drying up (Bloom) (Howlett) (Altenbaugh).

Today, the labor movement again finds itself in a period of stagnation and conservatism, divided on what strategies and programs will advance the cause of unions. The model developed at Brookwood Labor College deserves another look. In a time period of repeated labor setbacks and the Great Depression, Brookwood’s founders were able to recruit and train union leaders who went on to lead the largest and most effective organizing campaigns in US labor history. Brookwood accomplished this by recruiting true believers in the cause of organized labor and teaching them to create the world in which they wanted to live. Brookwood faculty developed a vibrant culture of solidarity amongst the students, focused the curriculum on action rather than grades, enlisted students in drama programs designed to reach the masses and deployed them into field work as a key part of the education experience. Brookwood’s use of academic and tool courses, as well as field work equipped graduates to go back to their unions with the skills to run them effectively, while simultaneously working toward the better and more just society they all believed possible.

Works Cited

“The Chautauqua Grows”. Brookwood Review (Nov 1935): 1.

Altenbaugh, Richard. Education for Struggle. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990.

Bloom, Jonathan. “Brookwood Labor College.” London, Tarr and Wilson. The Re-Education of the American Working Class. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1990. 71-84.

—. “Brookwood Labor College the Final Years 1933-1937.” Labor’s Heritage (1990): 24-43.

Brookwood Annual Report. Box 6, Folder: Brookwood College Papers, 1929.

Brookwood. Brookwood’s Contribution to the Labor Movement. Box 25 folder 1: Mark and Helen Starr Papers, 1933.

Brookwood Entrance Requirements. Box 6 folder 1: Brookwood College Papers, 1927.

Brookwood Guide for Students. Box 6: Brookwood College Papers, 1932-1933.

Brookwood Songs and Faculty Skits. Box 8: Brookwood College Papers, n.d.

Calhoun, Arthur. Labor Economics Curricula. Box 2, Folder 9: Brookwood College Papers, 1928.

Colby, Josephine. Detechnicalized Grammar Curriculum. Box 3: Brookwood Collage Papers, 1925.

College, Brookwood Labor. What is Brookwood? Box 25, Folder 8: Mark and Helen Norton Starr Papers, n.d.

DeCaux, Len. Labor Radical. Boston: Beacon Press, 1970.

Eisenmann, Linda. “Labor Colleges.” Eisenmann, Linda. Historical Dictionary of Women’s Education in the United States. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998.

Fine, Sidney. Sit Down: The General Motors Strike of 1936-1937. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969.

Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States Vol 9. New York, New York: International Publishers Co., Inc., 1991.

Goldstein, Malcolm. Political Stage: American Drama and the Theater of the Great Depression”. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Hentoff, Nat. Peace Agitator the Story of A. J. Muste. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1963.

Howlett, Charles F. Brookwood Labor College and the Struggles for Peace and Social Justice in America. Lewiston, New York: The Edwin Mellen Press, Ltd., 1993.

Katz, Michael. “The Role of American Colleges in the 19th Century.” History of Education Quarterly. Vol 23, No. 2 (1983): 215-223.

Lefkowitz, Abraham. Labor Legislation Curriculum. Box 4, Folder 20: Brookwood College Papers, 1936.

Lewis, Sinclair. “”Brookwood Remembered”.” Change Magazine (1981): 39.

Muste, A. J. The Essays of A.J. Muste, Edited by Nat Hentoff. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1967.

Muste, A.J. “”Shall Worker’s Education Perish?”.” Labor Age 18 (1929): 5-6.

Norton, Helen G. Student Survey. Box 13: Brookwood College Papers, 1931.

Norton, Helen G. A Survey of Students 1921-1931. Box 96, Folder 10: Brookwood College Papers, 1931.

Norton, Helen. Labor Journalism Course Outlines. Box 4, Folder 11: Brookwood College Papers, 1935.

Pollack, Katherine. Our Labor Movement Today. Katonah, New York: Brookwood, Inc., 1932.

Ransby, Barbara. Ella Baker and The Black Freedom Movement. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Report on Brookwood Labor College to Second International Conference on Workers’ Education. Box 12: Brookwood College Papers, 1924.

Report to Executive Committee. Box 6, folder 6: Brookwood College Papers, 1927.

Saposs. Trade Union Organization Curricula. Box 5, Folder 1: Brookwood College Papers, n.d.

Saposs, David. Readings in Trade Unionism. Worker’s Education Bureau of America, 1926.

Seidman, Joel. “Letter to Lloyd Cosgrove.” Brookwood College Papers, 23 February 1937.

Statement on Brookwood. Box 12. Brookwood College Papers, 1928.

“Student Body Minutes.” October 1932.